Content warning for discussion of death, grief, and mourning.

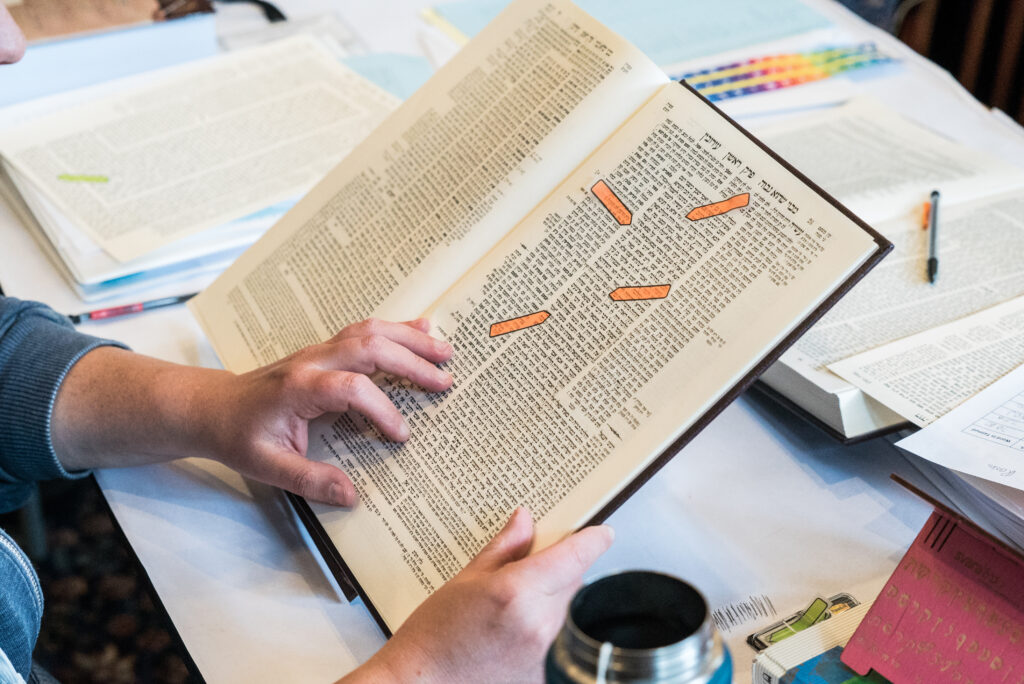

When I was a kid, my favorite pastime every Saturday was sitting in the corner of my synagogue and opening the cabinet full of picture books and graphic novels. These were full of little stories, fables, and, most of all, biographies of famous medieval rabbis. Sitting in that corner, Rashi became my friend, Shmuel HaNagid became my superhero, and Rambam became my guide. When I picture Rashi, I picture the version of Rashi I saw on those pages. Through those stories–full of wine, crusaders, Torah, and life–Rashi became real to me. When I later encountered him on the margins of my daf, I felt like I knew him.

Talmud is full of stories about rabbis, just like those comic books. But often, when I encounter a story about a rabbi with miraculous healing, laser eyes, or a just-too-convenient moral, it’s tempting to discount these stories as just fiction, just didactic fables, like Aesop or Kalila and Dimna. But as I was learning, I encountered a story that shifted my frame, and brought me back to that feeling of intimacy.

Many of us may know the delightful, tragic, queer aggada (a story in the Talmud about rabbis) of Rabbi Yohanan and Reish Lakish in Bava Metzia 84a: a bandit and a beautiful, beardless, twinky rabbi meet in the River Jordan. The rabbi takes the bandit into his care and tutelage and the bandit becomes a great rabbi in his own right. But on one fateful day, Rabbi Yohanan insults Reish Lakish by calling him a bandit, and Reish Lakish is so hurt, he becomes sick and dies. In the midst of Rabbi Yohanan’s intense grief, his rabbinic colleagues send him a replacement hevruta, Rabbi Elazar ben Padat. But when Rabbi Elazar comes to Rabbi Yohanan, Rabbi Yohanan criticizes Rabbi Elazar for only ever agreeing with him, not disagreeing with him as Reish Lakish once did. Rabbi Yohanan’s grief is so horrifyingly intense that it makes him scream and cry, so much so that the rabbis pray for his death, which he is mercifully granted.

On Berachot 5b, we have another series of stories about Rabbi Yohanan. Whether these are supposed to fit together with our Bava Metzia story into one “biography” of Rabbi Yohanan is unclear, but the two texts share a lot of similarities, especially in language. These three stories in Berachot flesh out Rabbi Yohanan, portraying him as a miraculous healer, though incapable of healing himself on his own. The third story fleshes out his relationship with Rabbi Elazar, his rebound hevruta:

רבי אלעזר חלש. על לגביה רבי יוחנן. חזא דהוה קא גני בבית אפל. גלייה לדרעיה ונפל נהורא. חזייה דהוה קא בכי רבי אלעזר. אמר ליה: אמאי קא בכית? אי משום תורה דלא אפשת — שנינו: אחד המרבה ואחד הממעיט, ובלבד שיכוין לבו לשמים. ואי משום מזוני — לא כל אדם זוכה לשתי שלחנות. ואי משום בני — דין גרמא דעשיראה ביר. אמר ליה: להאי שופרא דבלי בעפרא קא בכינא. אמר ליה: על דא ודאי קא בכית, ובכו תרוייהו.

Rabbi Elazar fell ill. Rabbi Yoḥanan entered to visit him, and saw that he was lying in a dark room. Rabbi Yoḥanan exposed his arm, and light filled the house. He saw that Rabbi Elazar was crying, and said to him: Why are you crying?? If you are weeping because you did not study much Torah, we learned: One who brings a substantial sacrifice and one who brings a meager sacrifice have equal merit, as long as he directs his heart toward Heaven. If you are weeping because you lack sustenance, not every person merits to eat off of two tables, one of wealth and one of Torah. If you are crying over children who have died, this is the bone of my tenth son. Rabbi Elazar said to Rabbi Yoḥanan: I am crying over this beauty of yours that will decompose in the earth. Rabbi Yoḥanan said to him: Over this, we should certainly weep. They both cried.

On a first read, this story seems uncomfortably superficial. We know Rabbi Yohanan is beautiful–in Bava Metzia, a shiny silver goblet full of red pomegranate seeds and a crown of red roses placed halfway between sun and shade represents only a semblance of his incredible beauty. But to weep over the loss of just physical beauty? Many of us have probably shed a tear or two over a pretty person, but that is hardly comparable to the grief of feeling that we have failed in our life goals, or the grief that comes with poverty, let alone the grief of losing a child. Rabbi Yohanan’s comment about child loss is layered, painful, and may seem extremely harsh. It is hard to make sense of without the earlier context of the sugya and a seminar on rabbinic theology. For the purpose of this short post, I’m going to put that aside.

On a second read, it’s worth focusing on a strange detail early in the story. Rabbi Yohanan’s bare flesh lights up the room–literally. This idea of bright light coming from exposed skin appears in two other stories in the Talmud, although both are from the exposed skin of women–just showing us more of Rabbi Yohanan’s fem side. Rabbi Yohanan is so beautiful that he lights up the room. And this is what I think Rabbi Elazar is weeping about. When we lose someone, a huge part of what we mourn is the way they light up a room, the way they show off their inner glam and glitz. We miss the way they uplift us and bring us joy just by being by our side.

Part of what I find so moving about Rabbi Yohanan’s stories is how his presence leaps across time. The memory of his life is so strong, so visceral, that we get a sense of his grace, his beauty, his sense of humor, his flaws, and his loves. In general, aggada represents a fragment of memory, passed down orally for generations, shared and reshared, and then written down into the Talmud we have today. Through aggada, we get a window into the lives of the rabbis, beyond just their legal opinions. This story, in which Rabbi Elazar fears the loss of Rabbi Yohanan’s beauty, preserves his light, his presence, and his very same beauty. By retelling the story, we keep Rabbi Yohanan’s beauty from fading into the earth.

It’s easy to think of the rabbis and people who appear in aggada as just characters in a story, especially when those aggadot include miracles and wonders that are unrealistic or fantastical, or when the stories are so clearly didactic that any plot just seems constructed. But I prefer to think of aggadot as echoes of real people, of their shining presences, their loves, their losses, and their Torah. When we read about Rabbi Yohanan, Reish Lakish, Rabbi Elazar ben Padat, Rashi, Rambam, and the rest, we get a window into a group of people whose presences continue to touch our lives almost 1800 years later. We get a small glimpse of their beauty, their glow, and their glam. Through aggada, queer, rabbinic ancestors touch our lives through the pages and through time. And that, I think, is a fantastic thing.