“Halakha is so rigid!”

“Judaism is all about binaries.”

“In Jewish tradition, it’s either one or the other.”

I often hear these claims in Jewish spaces, and they reveal an assumption that non-binary thinking is discordant with our tradition.

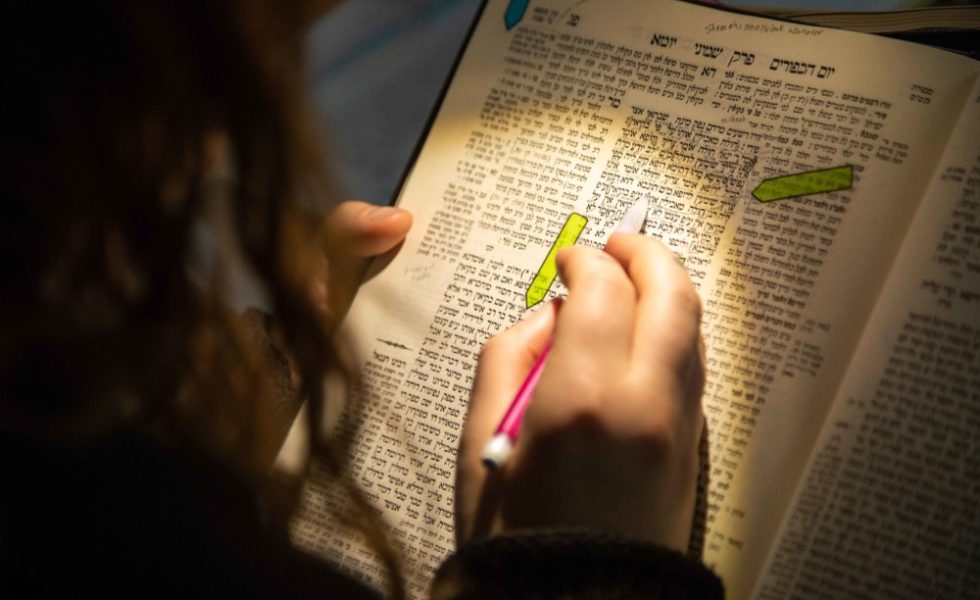

Somewhere, somehow, a very successful public relations campaign promoting binary Judaism must have made its way through our community. The binarization of our tradition is not a mystery. We know that there have been attempts throughout Jewish history to erase the beautiful, messy, and magical chaos that is foundational to Jewishness, whether for purposes of respectability and assimilation, or to incorporate the hegemonic religious ideologies surrounding our people. These forces have shaped our understanding of Judaism’s binary modes of thinking, but the more time I spend in the bet midrash, the more I realize that our tradition is one of the least binary, least rigid paths I’ve ever moved along.

Halakha is a window into the complex gradients of the world and our experiences. For every binary thought in our tradition, there are countless instances of liminality and expression which push us to think beyond binaries.

In halakha, there is no “morning.” There is alot hashachar (“rising of the sun,” the point at which the sunlight peaks on the horizon), neitz hachamah (“peaking of heat,” the moment when the top of the sun can be seen), and misheyakir (“from when he will recognize,” the moment when a person can recognize someone else—specifically not their closest friend—at a distance of a few feet). These distinctions are incredible and precious. To collapse them into the binary of day and night misses the juiciness and the beauty of the spaces in between, and the specificity that they each carry. The same is true for “evening,” which famously includes bein hashmashot (“twilight”), a period of time that sits between two days as both and neither, and has been a carved out as a holy, liminal, in-between space by R’ Reuben Zellman’s teachings1 and the “Twilight People Prayer”. This expansive time is also portrayed artistically, and with great care, by Dov Abrams in “Shaot Zmaniyot” (Al Daat HaMakom, 2004-present).2

Halakhic behaviors are not exclusively asur (prohibited) or mutar (permitted). Some are permitted before the fact, some are permitted after the fact; some are prohibited but there is no consequence for transgressing them; some are prohibited with a consequence, but only if the action was done intentionally; some carry consequences regardless of intentionality.

Halakhic language is a lexicon of ambiguity and multiplicity beyond binary thinking. Even the seemingly fixed categories of tameh (impure) and tahor (pure) are more expansive than a binary frame allows. Some forms of tumah require a mikvah (a ritual body of flowing water) to shift status. Some forms of tumah require waiting varied periods of time, washing clothes, and offering a sacrifice to shift status. Some forms of tumah can make other things tameh, and the instances are endless (those of y’all who have learned Sanhedrin 17a know this in your kishkes).

These are just tiny examples, but so much of the history of our tradition interrogates binaries and undermines linear thinking for the sake of more complexity and dynamism.

In SVARA’s Pedagogy Chaburah, we’ve been witnessing this complexity through our learning of a sugya in Masechet Eruvin about the halakhic prowess of Rabbi Meir:

אָמַר רַבִּי אַחָא בַּר חֲנִינָא: גָּלוּי וְיָדוּעַ לִפְנֵי מִי שֶׁאָמַר וְהָיָה הָעוֹלָם שֶׁאֵין בְּדוֹרוֹ שֶׁל רַבִּי מֵאִיר כְּמוֹתוֹ, וּמִפְּנֵי מָה לֹא קָבְעוּ הֲלָכָה כְּמוֹתוֹ? שֶׁלֹּא יָכְלוּ חֲבֵירָיו לַעֲמוֹד עַל סוֹף דַּעְתּוֹ. שֶׁהוּא אוֹמֵר עַל טָמֵא טָהוֹר וּמַרְאֶה לוֹ פָּנִים, עַל טָהוֹר טָמֵא וּמַרְאֶה לוֹ פָּנִים.

(Rabbi Acha bar Hanina said: It is revealed and known before the One who spoke and the world came into existence that there was no one like Rabbi Meir in his generation. And so, why didn’t they establish halakha according to his opinion? Because his colleagues could not fully understand his teachings. He would say about that which is tameh that it is tahor and express many facets and reasons behind his opinion. And similarly, he would say about that which is tahor that it is tameh and express many facets and reasons behind his teachings.)

תָּנָא: לֹא רַבִּי מֵאִיר שְׁמוֹ אֶלָּא רַבִּי נְהוֹרַאי שְׁמוֹ, וְלָמָּה נִקְרָא שְׁמוֹ רַבִּי מֵאִיר? שֶׁהוּא מֵאִיר עֵינֵי חֲכָמִים בַּהֲלָכָה.

(It was taught: Rabbi Meir was not his name, rather Rabbi Nehorai was his name [originally]. And why was his name [changed to] Rabbi Meir? Because he would illuminate [me’ir] the eyes of the sages in halakha.)

This tale about Rabbi Meir is one of my favorite examples of a Talmudic story that portrays halakha as a system that subverts binaries. At first, it seemed to us that the Talmud wasn’t sure whether Rabbi Meir’s subversion of categories and expansive thinking was too difficult for his colleagues to follow ( שֶׁלֹּא יָכְלוּ חֲבֵירָיו לַעֲמוֹד עַל סוֹף דַּעְתּוֹ) OR if it was enlightening for them (שֶׁהוּא מֵאִיר עֵינֵי חֲכָמִים בַּהֲלָכָה). The answer, of course, is both. As we unpacked this text together in the Pedagogy Chaburah, I was struck by how many of us felt so drawn to Rabbi Meir, and the degree to which he modeled the native non-binary power of halakha.

Rabbi Meir’s ability to see the tameh in the tahor and the tahor in the tameh—is an embodiment of non-binary thinking. It asserts that holding identities and thoughts that nurture beyond-the-binary, multivocal, multi-textured notions of truth is both tremendously destabilizing and profoundly illuminating.

Halakha pushes us to expand and refine our thinking. The refinement here, as SVARA’s Scholar-in-Residence Devin Samuels shared earlier this year, is not a process of distillation but an act of finding deeper clarity by recognizing the multiplicity in any moment:

The word that comes to my mind is clarity, right, like thinking of moving from a pixelated screen to HD; in the same amount of space, I can see intensely more detail. And in the emotional space, that’s nuance… It’s the ability to truly be present enough in the truth of what’s going on to see humanity in everything that’s going on around you.3

Halakhic discourse and practice is not about reifying a binary of yes or no; it is about creating space for clarity and authenticity in each moment of messy gradational life. Non-binary ways of thinking allow us to restore aspects of halakha that have been ignored for far too long. This isn’t a reimagining of halakha—this is halakha.

__________________________________

1 Zellman, R. (2006, September 21). The Holiness of Twilight. http://transtorah.org/PDFs/Holiness_of_Twilight.pdf

2 Al Daat HaMakom [Exhibition]. (2004-present). Kol HaNeshama, Jerusalem, Israel. https://www.studiodov.com/project/shaot-zmaniyot/

3 Soloman, L. (2022, January 7). Retraining Our Guts. Hot Off the Shtender. https://svara.org/retraining-our-guts/