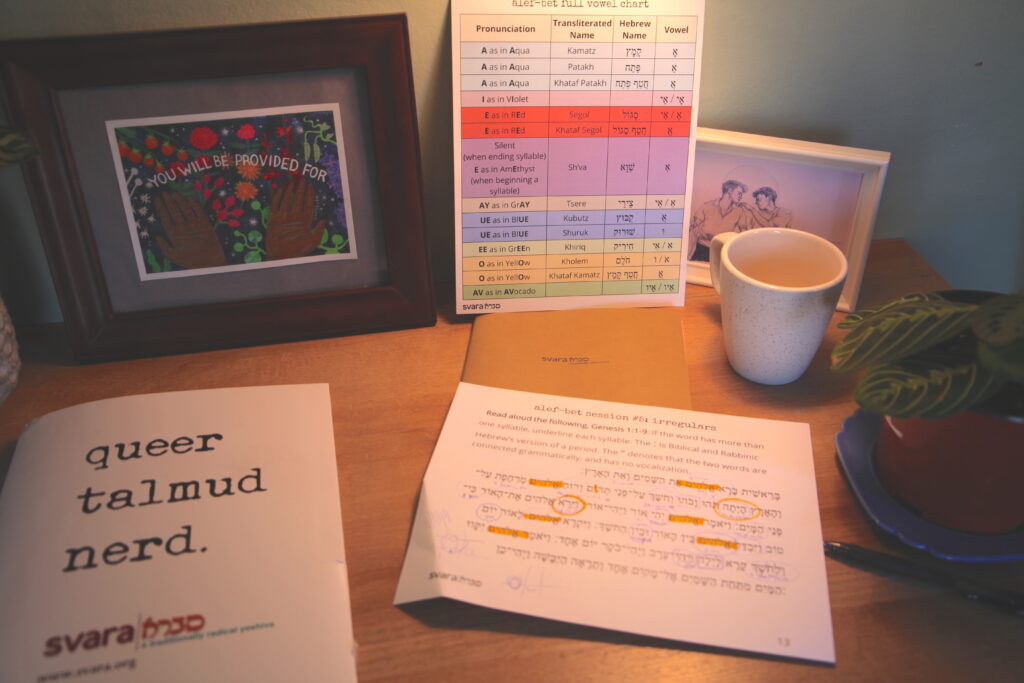

The artwork displayed in the image above was created by Molly Costello (left) and Adam Benedict (right). This piece is dedicated to my chevruta Elaina, and the bright shiny future of our friendship.

Last week, I accidentally watched the coronation service of King Charles III. I was on social media and got bombarded with footage of an event I immediately recognized but had no hope of ever understanding. I watched with disdain as an endlessly complex scene unfolded. Everything that was happening—from the obscure wardrobes, to the militarized choreography, to the untranslated hymns in Latin, to the abyss-like architecture—was a reminder of the violent symbology of colonialism. Get me outta here, I thought.

As a kid who attended a massive and charmingly dysfunctional public high school—one which failed to offer anything resembling world history—I spent my adolescence under the illusion that the British monarchy was a net-positive institution (yikes). It took graduating from college (something no one else in my family had done) and becoming radicalized by the political left (something no one else in my family had done) to understand how much of European history had been shaped by violence: violence that was being sanctioned, celebrated, and reenacted each and every day, not just on coronation day. I remember being at a party in my early twenties and standing quietly as a bunch of young angry queers were getting into a niche debate. They were agitating one another about the problematic nature of ethnographic documentaries, films that attempt to describe and evaluate the customs and cultures of entire peoples:

“Why do you think these documentaries are almost always narrated by British men?”

“I don’t know. Because they sound smart?”

“Have you ever wondered why you think British men sound smart?”

“Uh, I guess not.”

*dramatic pause* “COL-ON-IAL-ISM!”

Mine was a slow awakening, but thanks to the patience of some beloved friends and teachers, I eventually came to disregard my adolescent assumption that European monarchs were well-intentioned do-gooders. Fast forward more than a decade later and I’m begrudgingly watching the King of England’s coronation on my cellular telephone, grappling with the visceral discomfort I felt bearing witness to such inaccessible and problematic grandeur. I turned my phone off in defiance.

Moments later I turned my phone back on and headed for my browser.

“Coronation ceremony”

“Coronation ceremony what is happening”

“Coronation ceremony why is it so long”

“Coronation ceremony why do they do that”

Despite being fundamentally opposed to the whole spectacle, I am an unshakably curious person and I felt compelled to know more. Was there anything redeemable about this? Was there any small corner of the ceremony that wasn’t emblematic of the decimated sovereignty of millions of colonized people? My search results, however, were just as confounding as the ceremony itself. For starters, the Wikipedia page for the coronation of King Charles has more than 8,000 words and 231 citations. There are also hundreds of YouTube videos claiming to offer a step-by-step explanation of the ceremony, one of which began with the following disclaimer:

“Some elements of the ancient royal coronation ceremony are more than a thousand years old, so unless you’re a time traveler or an expert on royal history, you’re probably going to have some questions on what exactly is happening and why.”

Already in a bad mood, I snarkily thought to myself, “A thousand years? Are we calling that ancient? The Talmud is twice as old as that.”

The Talmud is twice as old as that. I was stunned by how quickly that piece of knowledge surfaced.

I know how old the Talmud is not because I am a time traveler or an expert of Talmudic history, but because I recently started learning at SVARA. I mean really recently. Six months ago I took our Alef-Bet Basics offering with the wonderful Ren Finkel, who made me feel like a genius even though I still have to look up every single letter to make sure my memory is correct (it often isn’t and, at SVARA, that is perfect). Not long after, I courageously registered for Queer Talmud for Beginner’s Mind, reassured by my fellow staffers that being a beginner was a sacred role to inhabit. During new SVARA-nik orientation, our Rosh Yeshiva (the one-and-only Benay Lappe), shared a simple but mind-blowing framework: if my chevruta, my learning partner, didn’t understand the text we were going to be unpacking in Queer Talmud for Beginner’s Mind, that meant I didn’t understand it either. The years I had spent in both secular and religious education spaces— years spent silently nodding when I was too afraid to admit I didn’t understand something—flashed before my eyes. SVARA introduced an unbelievable precedent for learning anything, let alone a notoriously complex and mystifying record written in a language I do not speak (or read, really), whose pages number in the thousands. If I could believe what Benay was telling me—that my learning and thus my liberation were going to be a collective process that depended on bringing people along with me (and hopefully being brought along by others)—then I could learn Talmud. And this spring, that’s what I did. I learned Talmud.

The folks who hold the gorgeous space of our Talmud offerings—the teachers, the fairies, the fellows, the techs, the captioners, the interpreters, the program staff—are unlike any folks I’ve ever encountered. Sure, I know plenty of kind, brilliant, reassuring, and helpful people. But the difference is that all of these SVARA folks have a deep commitment to making the obscure nature of our spiritual tradition joyful, empowering, and most of all legible. They pause their own journey to enter into mine, even if just for a moment. It is their guidance, their patience, and their encouragement that make me feel like I can keep going. They allowed me to feel more knowledgeable and empowered about Talmud, a twice-as-old and five-hundred-times-less-hegemonic tradition, than I did while watching the coronation ceremony of the King of England, a character I’ve probably had a conscious understanding of since I was in kindergarten.

My secular or religious education did not include any mention of Rabbi Matya ben Charash, but his words now live in my body thanks to my chevruta (Rose!), my teacher (Julie!), my fairies (Xava and noa!), my tech (freygl!), my captioner (Esther!), and all of my learning comrades in Queer Talmud for Beginner’s Mind. They all helped make the complexity of our tradition legible to me. The coronation ceremony, on the other hand, was characterized by a kind of inaccessibility that only those in power can assert: an insistence on keeping folks on the other side of sky-high, wrought-iron gates which guarded some self-proclaimed privileged knowledge. If we’re using this gate metaphor, arriving at SVARA felt much different to me. It felt like happening upon a small village that was cheerfully dismantling the gate which encircled it. In this metaphor, the SVARA folks look up from their work to wave at me. I wave back. “Hey! Come help us!” they shout. “We’re taking this down! It’s been here for a long time, but we don’t need it anymore! We’ll show you how to do it!”

Interestingly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, this isn’t how Talmud has typically been learned across the centuries. For most of history, Talmud has been held behind its own kind of gates, primarily accessed by a small group of learned people who were assigned male at birth. But what’s radical about what we do at SVARA is our orientation towards being the shapers of our own traditions and stories; our belief that the Talmud has been waiting for each of our unique voices to bridge the conversation across time and space and make new meaning. SVARA helps us to unpack the tools and tricks the Rabbis used in their time so that we can make liberatory change today. I am not claiming that Talmud hasn’t harmed people, because it most certainly has. The spiritual innovations SVARA-niks are making today are multidimensional responses to harm, dysphoria, and exclusion as much as they are responses to connectedness, joy, and belonging. I am, however, claiming that if more institutions with harmful legacies were courageous enough to invite people in for the sole purpose of reimagining a more just path forward, the world might be a better place. I’m thinking of the many people at SVARA who have invited me in. Our fairies immediately come to mind. At SVARA, fairies are the brilliant folks who “fly by” as we all learn together, answering questions and sharing new perspectives on whatever it is we’re unpacking. Fairies share knowledge, and reassure us that each and every question we ask is shaping our tradition. Let me tell you what a beautiful, life-giving comfort it is to know a fairy is on their way.

SVARA’s commitment to sharing knowledge is rubbing off on me. When people ask me where I work, I first ask if they know what a yeshiva is. That’s usually a good way for me to determine how I can frame SVARA in a way that makes sense. If they say no, I pull out a piece of paper and I draw a rough sketch of a daf, a page of Talmud that has a distinct, geometrical structure. “It’s a centuries-long conversation,” I say. “Right, yes, it’s different from the Torah. Halakha, yup, that’s sort of like the rules. Yup, exactly. I know. I know! It’s magic. We help people access that magic.” Can you imagine what the coronation ceremony could have been if someone was there, drawing a rough sketch of the throne, and the crown, and the scepter (can someone please tell me what the heck a scepter is), saying, “Hi, welcome! Yes, yup that’s right. These are such good questions. Do you know what a colony of occupation is?”

What a world it would be if all institutions, no matter how big and strong their gates were, took the time to stop and welcome folks in. Imagine how much we would learn, and how different we would feel. Imagine if they actually asked those folks they had let in to help take the gates down. But maybe that’s exactly why some institutions don’t do this. Maybe, if they took the time to unpack and explain each aspect of the coronation ceremony, of colonialism, of monarchies, of imperialism, of racist and violent exploits of precious economies and ecologies, they’d have to start thinking about whether they should still be doing it anymore. And just like learning at SVARA, the systems of old would be forever expanded. Imagine that.