As I imagine many of you have, I’ve spent the week in alternating states of heartbreak, anger, and deep inspiration, as we live through a national uprising in support of the Movement for Black Lives.

This past weekend, SVARA participated in Up All Night: Torah for Liberation and Revelation, a nation-wide Tikkun Leyl Shavuot (a ritual celebration of all-night Torah learning) hosted by eight radical and leftist synagogues* across the country. Weeks ago, when the organizers of this event conceived it, they didn’t know it would take place during an uprising. As it turned out, it was incredibly powerful to gather with over 500 people across time zones and cities, an ingathering of the leftist Jewish diaspora in the United States, at a time of intense and igniting political action against racist police violence.

It was also deeply painful. In the opening session, Rabbi Ariana Katz named George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, as only the most recent of so many lost Black lives at the hands of police, and acknowledged our state of communal mourning. Later that night, while teaching a Talmud workshop, I found myself in a quiet moment while participants were off in breakout groups. A SVARA-nik from Seattle sent me a private greeting in the chat. I replied, excited to see her there, and as she turned on her video, I could see the weariness in her eyes. She explained that she was “stopping in” between her shifts supporting the Seattle George Floyd demonstrations. I asked her what she was doing in her support role, and she described tracking areas of the city where white nationalists were reported to be perpetrating violence against people of color, and communicating with other protest leaders to clear folks out of those areas or avoid them altogether. “A little girl was pepper-sprayed by the police,” she told me. “It’s been horrible out here.”

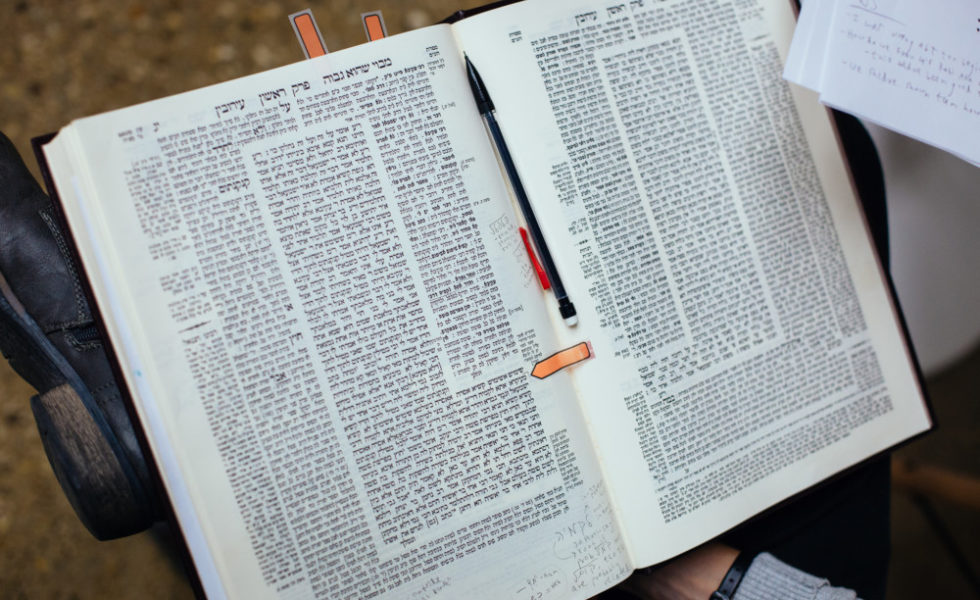

In our workshop, we learned a section of Pirkei Avot 6:2.

וְאוֹמֵר (שמות לב) וְהַלֻּחֹת מַעֲשֵׂה אֱלֹהִים הֵמָּה וְהַמִּכְתָּב מִכְתַּב אֱלֹהִים הוּא חָרוּת עַל הַלֻּחֹת, אַל תִּקְרָא חָרוּת אֶלָּא חֵרוּת, שֶׁאֵין לְךָ בֶן חוֹרִין אֶלָּא מִי שֶׁעוֹסֵק בְּתַלְמוּד תּוֹרָה.

And it says, “And the tablets were a work of G!d, and the writing was the writing of G!d, engraved upon the tablets” (Exodus 32:16). Do not read [the verse] as harut [‘graven’] but herut [‘freedom’]. For there is no free person except one who immerses in the practice of studying Torah.

The text refers to that paradigmatic Torah moment when Moses comes down Mount Sinai, having received the first set of tablets with the Ten Commandments on them. With the tablets in Moses’s hands we’re given this description: “And the tablets were a work of G!d, and the writing was the writing of G!d, engraved upon the tablets,” to teach us that the commandments were engraved by G!d’s own hand. As I read the verse I find myself asking: “What could the hand of G!d possibly look like, engraving those commandments onto a tablet of stone?” And since it’s impossible for me to imagine, I marvel at the fact that the text brings us this inconceivable image to grapple with and make meaning from.

The rabbis of the Mishnah wanted to find something different in this verse, a different theology altogether. The Torah is transmitted in written form without vowels, leaving the possibility for certain words to be mis-read, re-read, or read against the grain in the project of midrash (rabbinic interpretation). Without vowels, the word harut (חרות), meaning “engraved,” looks identical to herut (חרות), meaning “freedom.” One small vowel distinguishes one word from the other. “Don’t read it as harut, but rather as herut,” the Mishnah says, altering the meaning of the verse:

“And the tablets were a work of G!d, and the writing was the writing of G!d, freedom was upon the tablets.”

It’s a mysterious midrash. What exactly does it mean for freedom to be engraved upon the tablets? The Mishnah goes on to interpret: “For there is no free person except one who immerses in the practice of studying Torah”— linking Torah learning to freedom itself: perhaps freedom of intellect, free will to perform mitzvot, the redemptive power of spiritual practice and sacred text, or something else. I’m not sure, and I think the text is open to many interpretations.

But one thing feels clear: whatever came down from Sinai, whatever was revealed to Moses as Torah to live by and study endlessly, it was born out of freedom. Its raw material was freedom. Torah, according to this Mishnah, is liberatory. Torah miSinai is a Torah created out of freedom, in service of freedom, a Torah that generates the conditions of freedom. Anything used to oppress or dehumanize another person must not then be Torah, must not have been whatever was revealed and transmitted on that mountain by G!d to the Jewish people. When the tablets are merely harut, engraved, they are a tool, an object. When they are elevated to herut, they become the source of free people, bnei horin. They become a Torah that can transform the status of a person, that can set us free.

As we learned this text together on Saturday night, desperate pleas for freedom were being engraved onto the streets of our cities. A new kind of freedom is being carved out of the old system. A revolutionary cry is being heard across the country, for city councils, school systems, and all institutions to divest from, and defund, the police. The work that antiracist activists and abolitionists have done for decades and generations is being amplified and heard on an unprecedented scale, shaped by the voices of Black leaders, so many of them Queer and Trans. This cacophony of powerful voices includes the voices of Black Jews, and Black Jewish SVARA-niks, whose work we are so proud to support.

There is no Torah that is not a Torah of freedom, and if it’s not moving us towards freedom, it isn’t Torah. There is no learning Torah that does not result in us becoming bnei horin, a people rooted in a revolutionary understanding of liberation. A full and true liberation, that includes everyone. Our Torah must be a Torah that honors and works toward the freedom of Black lives. Our Torah must set us free from the entrapments of a violent and oppressive world. We’re going to need this liberatory Torah, depending on who we are, as we continue either to lead or support the work of this transformative movement, laboring so hard to honor the countless lives lost to white supremacy, and to unlock the chains our society is built on. “Freedom was upon the tablets.” May we return to the base of the mountain over and over again, in order to remember.

* Hinenu: the Baltimore Justice Shtiebl, Kehilla Community Synagogue in Oakland, The New Synagogue Project in DC, Kol Tzedek Synagogue in Philadelphia, Kadima Reconstructionist Community in Seattle, Congregation T’chiyah in Detroit, Kolot Chayeinu in Brooklyn, and Tzedek Chicago.