A few months ago, we added reciting the Shema to our toddler’s bedtime routine. Edie had experienced a language explosion and, one night, while we were singing Hashkiveinu, it occurred to me that she might be able to repeat back the words of the Shema. And so we went word by word. These days Edie says it on her own, often unprompted. Shemaaaaaaaah. Yisraeeeeeeel. Adonaiiiiiii. Elohei……nu Adonaiiiiiiii Echad. There is nothing sweeter than watching and listening to this recitation.

Edie’s nightly recitation of the Shema has been in the background as Mishnah Collective has begun our study of Masechet Berachot, which opens with a discussion on this very topic. When should we recite the Shema at night (Mishnah Berachot 1:1)? What does it mean to have Edie recite while it’s still day (yes, bedtime is early around here)? How should one recite the Shema (Berachot 1:3)? Reclining, or as they are? Many nights Edie recites while rolling around on the floor. Nonetheless, she is doing it, and we are witnessing it.

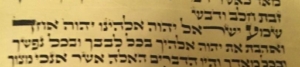

The question of “witness” opens up in the Mishnah through the word “עד / ad / until,” which comes from the root “ע-ו-ד / to turn, to continue, to exist.” In the hiph-il binyan, this root means “to declare one’s presence at a certain time,” or “to call upon as a witness,” and connects us to the noun “עד / ayd / witness.“ This connection is made more clear in a Torah scroll, where the Shema, also known as Deutoronmy 6:4, is written with an enlarged ayin at the end of the word “shema,” and an enlarged dalet at the end of the word “echad.” How might the practice of reciting the Shema shift in conversation with the writing in the Torah scroll?

In Masechet Sofrim 9:4, a non-canonical Talmudic text, we learn:

שמע ישראל (דברים ו) צריך לכתבו בראש השיטה וכל אותיותיו פשוטין ואחד צריך שיהא בסוף השיטה

The verse “Listen, Israel (Dev 6:4)” needs to be written at the beginning of a line, and all of its letters are stretched, and the word “one” (the final word in the verse) needs to be at the end of a line.

Comparing the image of a Torah scroll above the text of Masechet Sofrim, we might wonder when and why the writing shifted from having the whole verse written in large letters and on one line to having only the enlarged ayin at the end of “shema” and an enlarged dalet at the end of “echad?” The letters themselves spell the word “ עד / ayd / witness,” a role and experience open to wide interpretation.

We learn in the Kisse Rahamim, a late 18th century commentary written by Hayyim Joseph David Azulay, that:

שמע עין גדולה ודלת דאחד גדולה הוא עד כמו שאז”ל

ואפשר לרמוז כי ע”ד ר”ת ענוה דיבור לומ’ שאם יש לו ענוה אין יצה”ר שולט בו.

In the word “shema / listen” the ayin is large, as is the dalet in the word “echad / one.” This is “ayd / witness,” like we see in [the book] Ohr Zarua. This is a hint to the phrase “ענוה דיבור / humility of speech, which is to say that if a person has humility, the evil inclination will not rule over him.

Hury lifts up that the emphasis of these two letters is purposeful, that they have something to teach. For Hury, it is a reminder that we should exercise humility in our speech, a deepening of the meaning of the word “shema,” listen. These letters are large so that we might be reminded that listening requires us to refrain from speaking, that humility and quiet are ways to experience the unity in the world or to help work towards that unity.

Another interpretation: In the Talmud (Shabbat 104a) we read a story of young children entering the Bet Midrash and sharing interpretations of the letters. Ayin stands for עֲנִיִּים / poor and dalet for דַּלִּים / needy. These letters call our attention to those in our society who need care and material resources.

While Tractate Sofrim offers a scribal practice that sets the words of the Shema apart from the rest of the Torah, the practice of Kisse Rahamim allows us to imagine these words as a call to witnessing, a call to knowing when it is our time to speak, and a call to recognize those who are less fortunate. In his commentary on Deuteronomy 6:4, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch adds another layer, writing that “one generation shall tell another about Gd’s revelation, one community shall attest to another, and by means of this tradition the revelation will remain the indisputable basis for all the thoughts and actions of every man of Israel for all eternity.” While one might disagree with Hirsch’s latter statement regarding revelation, Hirsch frames the words of the Shema as a spiritual technology that connects us to each other and Mt. Sinai.

Each of these can enhance our experience of the liturgical practice of reciting Shema, understanding it as a collective reminder of the work necessary to bring about the unity of Gd, the world to come, collective liberation, embedded in the essence of our liturgical life.

These days, I’m not praying with the traditional liturgy much, so Edie’s recitation may be the only time the Shema is said in our family during the day. Sitting on the play mat next to her big kid’s bed (“not a crib, dada, a big kid’s bed”), Naomi and I finish singing Hashkiveinu and Edie picks up. We are teaching Edie to recite the Shema because it represents the best of what Judaism and religious community can be — a force for deep connection and radical care for the sake of creating a world where all people can thrive. Clutching her goat stuffie, the words roll out of her mouth. Shemaaaaaaaah. Yisraeeeeeeel. Adonaiiiiiii. Elohei……nu Adonaiiiiiiii Echad. In the immediate next moment, in that precious quiet, my heart is open and everything is perfect.