This HOTS is dedicated to the memory of Rabbi Dr. Richard Ruth, z”l

This spring our SVARA shiur has been diving deep into pikuach nefesh, the concept that one can supersede other mitzvot in order to save someone’s life. After our Mishnah presents a case in which one can break Shabbat in order to save someone (or, one’s obligation to save a life supersedes the obligations and regulations of Shabbat), the Gemara asks: from where do we know that pikuach nefesh supersedes Shabbat?

A long list of early rabbis (Tannaim) respond to the question with complicated, multi-layered proofs. At the end, an Amora, a sage born a few hundred years later, Shmuel, says that if he’d have been there, his proof would be better than all the others. Here’s what he does:

First, Shmuel quotes a piece of Torah from Leviticus 18: וחי בהם / v’chai bahem. In the context, G!d is saying that the people of Israel will live by G!d’s laws. In the most literal sense, what it means to ‘live’ by them is to live according to the laws, to practice them.

And what does Shmuel do with this? He takes this sound byte of ‘v’chai bahem’ and unlocks a whole new meaning:

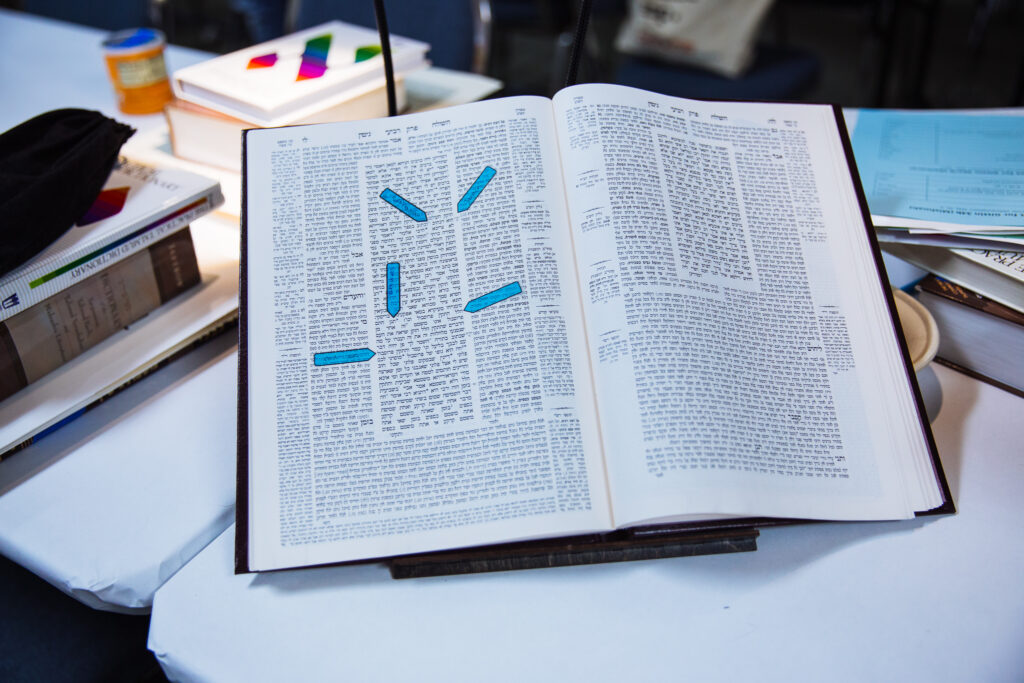

Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 85b

וחי בהם ולא שימות בהם

“Live by them,” and not die by them.

Shmuel is saying that when you read “live by them” in the Torah, what you should understand is that staying alive – or not dying – is a critical component to fulfilling the commandments. And so, mitzvot only apply if you will continue to live doing them – if keeping them would kill you, you shouldn’t do them! It is a radical change to look at this text and read it differently, and it’s a catchy, pithy line: live by them, and not die by them. It’s no surprise that this powerful line and concept has lived through the generations to become a cornerstone of Judaism today.

Digging deeper into the way this verse has been understood over the generations, our shiur encountered Rebbe Nachman’s commentary. He takes both the Torah’s “וחי בהם” as well as the commentary of the Talmud, “ולא שימות בהם” together as his source text to support his claim:

Likutei Moharan, Part II, 44:5

וְעַל אֵלּוּ הַמְדַקְדְּקִים וּמַחְמִירִים בְּחֻמְרוֹת יְתֵרוֹת, עֲלֵיהֶם נֶאֱמַר: וְחַי בָּהֶם, וְלֹא שֶׁיָּמוּת בָּהֶם, כִּי אֵין לָהֶם שׁוּם חִיּוּת כְּלָל, וְתָמִיד הֵם בְּמָרָה שְׁחֹרָה, מֵחֲמַת שֶׁנִּדְמֶה לָהֶם שֶׁאֵינָם יוֹצְאִים יְדֵי חוֹבָתָם בְּהַמִּצְווֹת שֶׁעוֹשִׂין, וְאֵין לָהֶם שׁוּם חִיּוּת מִשּׁוּם מִצְוָה מֵחֲמַת הַדִּקְדּוּקִים וְהַמָּרָה שְׁחֹרוֹת שֶׁלָּהֶם

And about those who are exacting (medakdikim) and rule strictly with lots of extra stringencies, it is said: “and live through them” (Leviticus 18:5), and not to die by them (Yoma 85b). For they have no vitality at all and are always melancholy, because it seems to them that they don’t fulfill their religious obligations with the mitzvot they perform. And they have no vitality from any mitzvah on account of their exactitude and melancholy.

We see another radical and innovative layer on our sugya R’ Nachman says: when we see “and live by them,” we’re not just talking about life or death situations, we’re talking about living a full, deep life. R’ Nachman claims that those who are focusing too much on the minutia in pursuit of creating more and more stringency might always feel like they aren’t fulfilling the commandments. And if you don’t feel like you’re fulfilling the commandments, you’re not going to be fully living your life. That’s a big claim!

In some ways, I love how Rebbe Nachman expands this text. He said “listen, I know that you might’ve been talking about a life-and-death kind of ‘live by them’ to help you figure out how to act – but that’s not enough. To truly live by the commandments means living in a deeper sense – to feel like you’re really living your life fully.” As queer folks, we know that fighting for our lives and the chance to live out our big, beautiful, full lives are both matters of pikuach nefesh.

At the same time, R’ Nachman is also giving this process of dikduk, of close examination, a harsh critique. Hey R’ Nachman, we love the minutia here at SVARA! The SVARA method uses close, exacting examination as a source of power, a tool for connection, and an opportunity for creativity. We even call our type of learning a spiritual practice. What would R’ Nachman think about our inside / outside translations?

I’ve been thinking about this text through the lens of R’ Dr. Richard Ruth, a beloved SVARA-nik who passed away this month. Richard was a dedicated chevruta, a teacher of Talmud, and a mentor to many in his community. One thing I admired about him was his ability to hold deep gratitude alongside a passionate and meticulous push toward better accessibility systems, pushes that brought us to many of the accessibility practices that we have today at SVARA. Richard was always ready with a suggestion or a noticing to share for how we could live our values more fully. And in the same breath, he always made note of the nisim b’chol yom, the miracles of every day, whenever we spoke; he shared when spring was on its way, that his learning was a taste of olam haba, and abundant blessings.

Richard had cultivated the right balance in himself for dikduk and spaciousness to fill his life to the fullest, but I think that Richard also did something more radical – he crashed the framework to begin with. Richard was euphoric using dikduk to push new possibilities into view, both in the beit midrash and outside of it. Rebbe Nachman said that live by them meant living a full life. Richard showed that one could find the fullness of life not by avoiding a close examination, but by diving right into it as an ongoing spiritual practice with presence, connection, and joy.

One time after a shiur, Richard sent me this note: All of this learning is alive. The other word coming out of [the root we learned in shiur] is bonei, building, which is what we are doing together – living the mishna. Jastrow has no monopoly on bonuses, eh?

A Jastrow bonus is when you find the reference for your text in the dictionary – you get a “bonus” in your word-by-word translation work when you get to see a whole phrase from the text you’re learning laid out in Jastrow’s definitions. But to Richard, the phrases showed up everywhere in his daily life. Everything was a bonus. He had bonuses all the time.