Origin stories are powerful. They give names to our ancestors. They lift up voices, honor the courage and power of individual actions, and let us find heroes in our past. In the blur of what movements sometimes can look like, I find power and feel endless gratitude for identifying the rad, Queer ancestors that have so materially transformed how I am able to live my life.

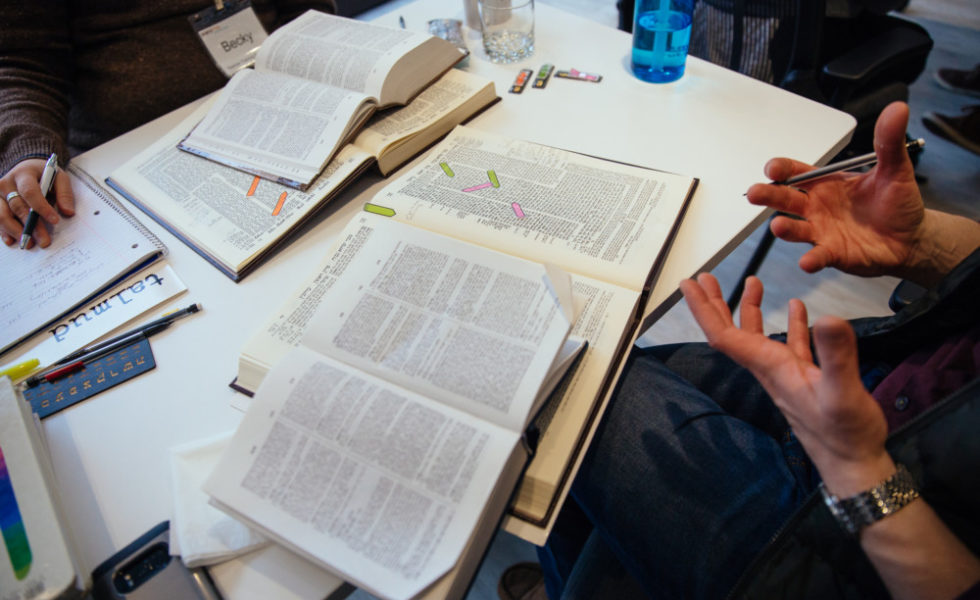

This summer, I’ve had the blessing of Fairy-ing in SVARA’s Summer Shiur, a weekly bet midrash for SVARA-niks to deepen their regular practice of learning, where we have explored a section of Talmud from Masechet Berakhot 26b that is, on the surface, an argument around the origin of prayer:

רבי יוסי ברבי חנינא אמר תפלות אבות תקנום רבי יהושע בן לוי אמר תפלות כנגד תמידין תקנום

Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, said: prayers were instituted by the biblical Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob). Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: prayers were instituted based on the daily sacrificial offerings [outlined in the Torah].

The argument is presented: does prayer come from the Patriarchs, or was it an invention of the Rabbis, an innovation they created to update an old practice––making sacrifices–– that was crashing?

In so many ways, it is clear that the structure of praying Amidah three times a day mimics the daily sacrifices of the Temple. We see it in the content of our prayers, and some services are named directly after certain sacrifices (mincha and musaf are two of them). And yet, the Talmud offers a series of unlikely examples in which they argue that our ancestors, Avraham, Yitzchak, and Ya’akov, institute the morning, afternoon, and evening prayers respectively.

תניא כוותיה דרבי יוסי בר׳ חנינא אברהם תקן תפלת שחרית שנא׳ ”וישכם אברהם בבקר אל המקום אשר עמד שם“ ואין ”עמידה“ אלא תפלה

It was taught [in a baraita] in accordance with Rabbi Yosei, son of Rabbi Ḥanina: Abraham instituted the morning prayer, as it was said: “And Abraham woke up early in the morning to the place where he had stood” (Genesis 19:27), and “standing” is nothing other than prayer.

In the text itself, Avraham does not plainly appear to be praying—it seems as though he is simply standing. But the author of this teaching takes this moment and argues that we should see it as prayer. The text continues to do this with Yitzchak “conversing” for mincha, afternoon prayer, and Ya’akov “arriving” for ma’ariv, the evening prayer. While it is clear in the Torah itself that these ancestors were not praying in a recognizable way to us, the Talmud threads these ideas together, connecting our patriarch’s seemingly mundane actions to our daily rituals.

How could these seemingly singular and mundane events translate to our daily ritualized version of prayer? At SVARA, I have learned to ask: Why would the stamma, the editors and compilers of the Talmud, include this text? What point are they trying to make? What’s at stake here?

One SVARA-nik in our Summer Shiur, Alex, pointed to how singular moments and actions have swelled into collective ritual, practice, and movements that may have seemed unimaginable at the time. Alex said, “you never know if something you do is going to be the first day for the rest of your life, or just once.” They present a challenge for us: how are we living our lives with the awareness of that potential? In what ways are we setting the example, practice, or system that will grow and transform for generations to come?

That sentiment is so powerful, and also scary. A small, random thing I do could set off patterns, rituals, movements? I freeze up when I think of it. But when I think about how movements work, I remember that in alchemy with that “one person” or that “one moment,” there are teams of organizers working for decades, laying the groundwork, crafting the narrative, and working out the kinks of what our future can look like. In the case of our sugya, this team is the Rabbis, and they are laying the groundwork for a new way of practicing Judaism as the Temple model is crashing. At the conclusion of our sugya, in response to the question, “Is prayer derived from the Patriarchs or the Rabbis?” we read:

תפלות אבות תקנום ואסמכינהו רבנן אקרבנות

The Patriarchs instituted the prayers, and the Rabbis leaned them on [the structures of] daily sacrificial offerings.

The sugya resolves that both the Patriarchs and the Rabbis make prayer happen. Singular moments or individuals (in this case, the Patriarchs) can provide inspiration, and the collective (in this case, the Rabbis) can weave these moments into our narrative for new systems and change.

I think about the current uprising in my city of Oakland. With a seemingly sudden swell of support and action from the community, in response to the murder of George Floyd, the Oakland School Board unanimously agreed to eliminate its police force on school campuses. And, this didn’t come out of nowhere. For almost a decade, the Black Organizing Project has been laying the groundwork for this change with its BOSS (Bettering our School System) Campaign, and this summer they used this moment to weave in the story of George Floyd and organize thousands of Oakland residents to tip the scales.

And, understanding how movements and rituals come out of a tapestry of individual actions and collective power, I feel relieved to think of myself as a weaver crafting the story, rather than a lone actor under a microscope. Knowing that this win was the combination of a singular event and a group of smart, rad people with a vision for change encourages me to think about how I can reach backwards–– drawing inspiration from an ever longer lineage of activists–– and also reach across–– seeing the collective of people at work to turn a single action into a movement.

Our movements and rituals do not come out of nowhere, and the actions weren’t spontaneously made in isolation. They came out of lineages and collectives of people who, each and every one of them, were needed in order to make the thing happen. And Baruch HaShem, thank God, I get to be in this rad, Queer community and live within a brilliant, diverse collective to imagine and create what’s next.

—–

With gratitude for Alex Dillon for chevruta-ship and an inspiring reading of this text.