This is the last Hot Off The Shtender of 5783.

Rosh Hashana allegedly marks the birthday of the world, but it also marks my own Jewish birthday. Technically a convert, my Jewish path began when I was nine years old. (Pithily, I maintain that I was born Jewish, just not to a Jewish mother, who even if she had been a Jew would have been more Emma Goldman than Eshet Chayil/a ruby amongst women.) I was in my 5th grade classroom (I can still picture exactly where my seat was) when our teacher, Mrs. Rex—one of those young and very beloved teachers—told us that she was not going to be at school the next two days. She explained that she wasn’t ill, and we didn’t need to bring her a get-well card or anything like that. Rather, she explained, she was Jewish and she would be attending a religious ceremony to mark the Jewish New Year. She wrote “Rosh Hashana” and “New Year” on the chalkboard. I found myself focusing intently as she described a ritual that both celebrated the arrival of a new year and encouraged folks to think about things that went wrong in the past.

She went on to say that about a week later she would be gone again for another holiday, and this time she wrote “Yom Kippur” and “Day of Atonement” on the board. She explained that atonement was how people fix their sins and mistakes, (she added “sins” and “mistakes” to the board), and that that was the whole point of Yom Kippur. She then told us that Jews atoned when they opened their hearts by praying and emptying their bodies by fasting (“prayer” and “fasting” were also rendered in chalk) and made things right by apologizing and forgiving. She continued to elaborate, both verbally and calligraphically: No food, no water, and nothing but prayers, apologies, and forgiveness for a full 24 hours. And afterwards, she said, you feel really good and get to start the new year with a clean slate and everyone shared a delicious break the fast, which is, she said, where the word breakfast comes from. By the end you felt really good because you got to start the new year with a clean slate. She then wiped the blackboard clean for dramatic effect.

As she explained, I felt my ears prick up. What she was saying made perfect sense to me, and I knew I wanted in. At nine years old, I had already been exposed to more than my fair share of sinful human behavior. Drugs, alcohol, violence, chaos, stink, destruction, unpredictable outbursts, irrational actions, persistent danger, utter disregard for self and other and, no joke, two freaked out squirrel monkeys, formed the matrix of my family at that point. To learn that there was a religion that group of people who recognized that life is people are messy and which set aside time for to do a communal spiritual and physical cleanse to and start over fresh?? I mean!! Yeah, bring it!!! I fell right in love with that idea. I walked home energized, and as soon as I walked in the door I asked my mom, who was only mildly tipsy at that hour, “Mom—What’s a Jew?” And, despite her early failings as a parent, she got a few things really right, and this response was one of them, without dropping a beat she said, “Weeeeellllll, according to Ben Gurion, a Jew is anyone who caaaalls themselves a Jew.” A huge smile spread across my face. I said, “Well, then I’m a Jew.” Her thick, black, Irish eyebrows shot up nearly to her hairline, she took a drag on her unfiltered Raleigh cigarette, blew out a smoky stream and said, “Hm! Well, moooore power to ya, kid.”

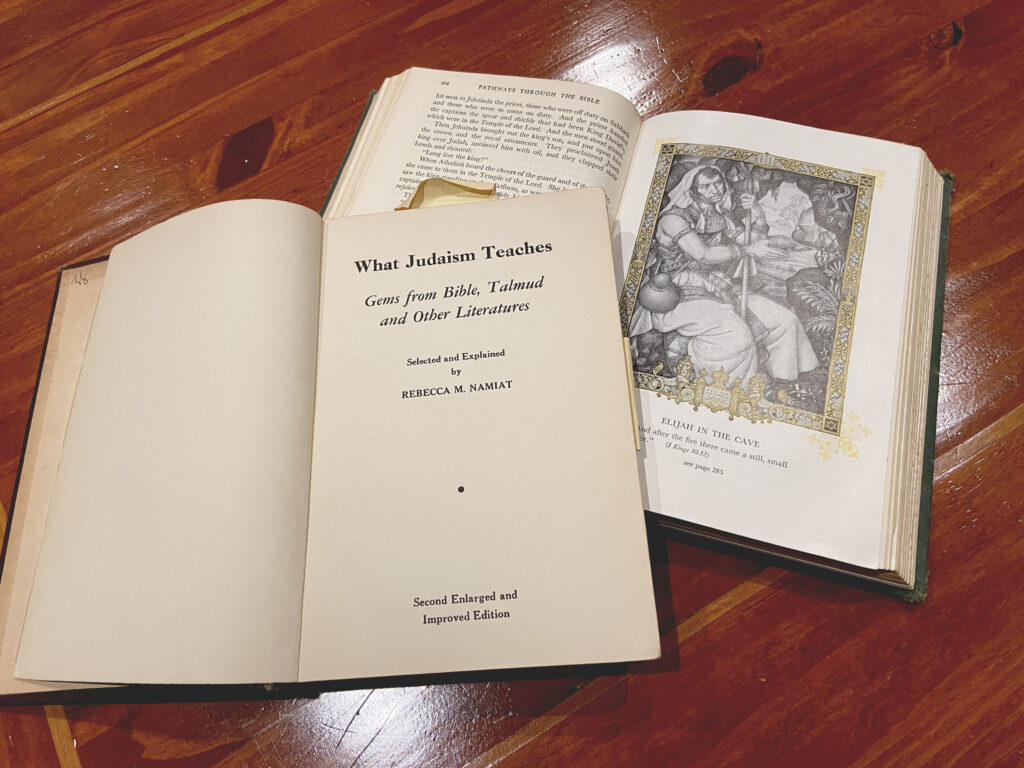

I began learning on my own before I hit double digits. I checked out everything the Venice Public Library offered under the heading Jewish. I read Heschel (didn’t understand a word that first time around) as well as Martin Buber’s Tales of the Hasidim and The Diary of Anne Frank—much more accessible to the pre-teen set. A friend’s mom, another brilliant train wreck, when she learned of my spiritual journey, gave me Rebeca M. Namiat’s 1940 classic “What Judaism Teaches,” which I pored over.

As a tween in the 1970s, I often babysat for a Jew-ish family across the alley. The kids were a handful, but once they conked out, I had time to copy recipes from a Jewish cookbook that resided between “The Joy of Sex” and “Be Here Now.” I can’t remember the book’s title, but it had what turned out to be the world’s most challenging challah recipe**. I’d never made bread before, nor had I ever tasted challah. But I’d learned that challah was essential for Shabbat and since there wasn’t a market anywhere nearby that sold it, and despite the class 5 level baking difficulty, I intrepidly tried my hand at making it.

It took me about a year to get the rich dough to braid, rise, and bake properly. Eventually I was turning out a dense but fluffy, decadent and sensuous, honey perfumed, and immensely satisfying loaf. To this day the feel and flavor of that challah is THE taste of Shabbat for me. Too young to join a shul, I pursued Jewish culture like a hawk–I got my hands on some Doc Brown’s Cel-ray tonic and convinced myself that I liked it; I tracked down a decent falafel stand and a pretty darn good bagel shop. I learned to sing Jewish tunes songs from corny recordings of Isreli folksongs.any Jewish LP I could find. I fell in love with Barbra Streisand (and I’m still there!), discovered how to cuss in Yiddish, memorized Hebrew blessings, and learned to lie about all of it in English. By the time I was b’mitzvah age, I knew enough to pass. My original last name was Johnson, so when one of my Jewish friends would incredulously say, “You’re JEWISH?” citing my last name as proof positive that it I could not possibly be a landsman, I’d retort “Well, like, my maternal grandmother’s surname is Schoenberg, OK…” True fact, but I didn’t elaborate that she married a Lutheran of German descent, so I just let them do the math without that part of the equation. Meanwhile, I looked at them with my head cocked, eyes rolled, and a “Hello, duh!” expression on my face. Of course I never actually said I WAS Jewish, because well, thou shalt not bear false witness, just sayin’.

Food, music, Yiddish, and jury-rigged ritual was great, but the pedal really hit the metal when I started learning Torah. It began with a ten-cent garage sale find: Mortimer J. Cohen’s “Pathways Through The Bible”, which is a simplified, with younger readers in mind, version of the TaNaKh, ironically with some pretty racy and intense illustrations by Arthur Szyk. I read a section every night before I went to sleep. When I got to the end, I instinctively went back to the beginning and started all over again. I loved how reading it made me feel, how relatable it was, and especially finding the stories that spoke to all of me—a queer poor kid, growing up in a slum by the sea that was by that time slowly but surely getting gentrified. I saw myself in Abraham and Sarah who had to leave their hometown to find themselves. I could relate to Joseph and Moses, and their multiple identities. I knew exactly what Moses was going through every time he lost his temper. I was thrilled when I stumbled upon the unvarnished accounts of David and Jonathan, and Ruth and Naomi’s unabashed queer love. And of course, Devorah, incredible military genius and spiritual prophet, and her Zen warrior counterpart, Yael.

In high school, I started reading standard translations of the TaNaKh, which were considerably grittier than Pathways. I was comforted and felt seen by The Torah’s unflinching assessment of humanity. I related to the tumult and trauma of the early transient ancestors, the firebrand activism of Moses—his erratic moods and emotional meltdowns, and how the old bastard worked his whole life trying to get to the promised land only to die within spitting distance of the goal. I found the Torah’s displays of xenophobia, chauvinism, patriarchy, violence, and treachery to be accurate and honest reflections of the world into which I was born. And to this day, I’ll take honesty over denial and avoidance. It remains my strong belief that people are, and will always be, a red hot mess—but that doesn’t mean we aren’t also glorious, beautiful, stunning, and awesome in our better moments. I could never trust a tradition that claims perfection whereas Torah commands us to slaughter the unblemished critters and eat it as a form of worship. Now, that’s my kinda religion.

By this time my mom had gotten sober, kicked my disastrously broken step-dad out, learned to drive, and had gotten herself a decent, union job. She got involved in local politics and was being embraced for her wit, will, and wisdom by her co-workers and the old guard Venice Beach artists and activists. She was engaged in the movement to slow down the rapid real estate development that was just as quickly displacing the longtime, low-income beach residents. But her most amazing act of t’shuvah was when she started volunteering at the local battered womens’ shelter, offering her non-judgemental, no bullshit, powerhouse support to those who were just stepping out on their own road to recovery. She was suddenly fun to be with, edgy, quick with a pithy comeback, connected, and most of all, totally awake.

While the Torah recognizes that holiness infuses the world, it simultaneously teaches that it is upon us to untangle it from the profane. God isn’t here to fix things for us. Quite to the contrary, God is doing Their best to just be what They will be, too. And that is not only what drew me to this path, but it is also what keeps me on it. The simple and ongoing task of choosing to show up knowing that mistakes will be made, emotions will run hot, injury will be caused, harm will be suffered, and change is always possible, in fact it is inevitable.

As the new year looms, I’m thinking about my mom, of blessed memory, and her remarkable transformation and full embodiment of what Judaism calls tshuvah, the central activity of the new year. I’m remembering Mrs. Rex and how she, by unabashedly owning her Jewishness, inspired mine. And I’m so grateful to her simple teaching that where there is prayer, apology, and cleansing there is hope for a better future, yet another way of enacting t’shuvah. As the old year phases out, I’m remembering with great respect my many teachers under whose wings I have learned, been challenged, and got to see what it feels like to soar. It’s a titch cliché and seasonal, but the piece of Torah that I’m poring over these days is by me, really the essence of the path.

כִּי הַמִּצְוָה הַזֹּאת אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם לֹא־נִפְלֵאת הִוא מִמְּךָ וְלֹא רְחֹקָה הִוא׃

לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִוא לֵאמֹר מִי יַעֲלֶה־לָּנוּ הַשָּׁמַיְמָה וְיִקָּחֶהָ לָּנוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵנוּ אֹתָהּ וְנַעֲשֶׂנָּה׃

וְלֹא־מֵעֵבֶר לַיָּם הִוא לֵאמֹר מִי יַעֲבר־לָנוּ אֶל־עֵבֶר הַיָּם וְיִקָּחֶהָ לָּנוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵנוּ אֹתָהּ וְנַעֲשֶׂנָּה׃

כִּי־קָרוֹב אֵלֶיךָ הַדָּבָר מְאֹד בְּפִיךָ וּבִלְבָבְךָ לַעֲשֹׂתוֹ׃ {ס}

רְאֵה נָתַתִּי לְפָנֶיךָ הַיּוֹם אֶת־הַחַיִּים וְאֶת־הַטּוֹב וְאֶת־הַמָּוֶת וְאֶת־הָרָע׃

…

הַעִדֹתִי בָכֶם הַיּוֹם אֶת־הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֶת־הָאָרֶץ הַחַיִּים וְהַמָּוֶת נָתַתִּי לְפָנֶיךָ הַבְּרָכָה וְהַקְּלָלָה וּבָחַרְתָּ בַּחַיִּים לְמַעַן תִּחְיֶה אַת וְזַרְעֶךָ׃

Surely, the instruction which I instruct you today, is not too difficult for you, and it is not distant.

It is not in the heavens, that you should say, “Who among us will can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, so we can do it?”

Nor is it beyond the sea, that you should say, “Who among us will can cross to the other side of the sea and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may do it?”

Surely, this matter thing is very close to you—it is in your mouth and in your heart, to manifest do it.

See, I set before you this day, life and goodness, death and adversity.

…

I call heaven and earth to bear witness with you today: Life and death I have given you, the blessing and the curse. Choose life—in order that you and your offspring might live.

D’varim 30:11-15, 19

Or to quote my mom, “Freedom is a matter of choice.”

May we be free and courageous as we move into this transition time. May the path we have chosen continually teach us to hone our edge no matter how dull it has become. May the journey be salty and sweet, bitter and tangy, complex and savory, satisfying and delicious. May our stories inspire and may we redeem even the worst moments of our lives. May we find forgiveness and healing. And may this new year bring us closer to exactly who, and what, and where we were meant to be. Happy birthday friends. Shana tova, u’meitukah.

—

**Jhos’s 1970’s Babysitting Challah

2 packages dry yeast

4 tsp sea salt

¾ C. Honey

1 ¾ C. very warm water (if the honey is cold, make the water hotter)

2.C. unbleached white bread flour

1 ¼ C. oil (I find that a light flavor is better—I use safflower)

3 large eggs

5-8 more cups of flour (you can sub in up to 2 C. whole wheat)

In a large bowl, mix the water, honey and salt—when all is dissolved sprinkle the yeast on top and let bloom (I usually cover the bowl with a cloth and put it in a warm spot)

Once the yeast has become kind of foamy, add in 2 cups of flour—then add in an egg, mix until it is fully incorporated, then about 1/3 of the oil and mix that until it is totally incorporated—repeat this process, until all the eggs and oil have been mixed in, at this point it should be batter-like with a silky consistency.

At this point you should wash you hands, remove all rings, bracelets, roll up your sleeves, and tie back your hair if you still have some, and do a few arm, neck, shoulders, and back stretches….

Then begin adding the remainder of the flour, one heaping cup at a time, mix in using a large whisk, when it gets too stiff switch to a large wooden spoon, and finally when it starts to come away from the bowl switch to your hands, turn the dough out onto a very heavily floured board or counter and begin kneading—the dough is very sticky, and requires a light touch—I usually make sure there is a lot of flour both under the dough and on top and with quick strokes I both mix in the remaining flour and knead until the dough is smooth and round. This dough should be very silky in texture—

Oil a large bowl and put the dough ball in it—cover and let it rest and rise in a warm place until it has doubled in size (usually a few hours)

Punch down the dough and knead again—(if time allows, let it rise again for a second time, but if time is short you can skip this second rising and often still get great results.)

Punch down again, knead briefly, cut the mound into two pieces—set one aside (use flour to keep it from sticking), take one round and cut it into 3 pieces, take one of these pieces, knead it briefly and then begin rolling, gently tugging, squeezing and otherwise convincing it to become a rope about 2.5 feet long which you then lay on a parchment lined, full sized cookie sheet, the long way (it should hang over the ends by a few inches on either side). Repeat this with the other two pieces, and then braid—I start in the middle braiding ‘over’ in one direction, and ‘under’ in the other direction….

Repeat with the other mound.

Let the two braided loaves rise in a warm, dark place on the cookie sheets for another hour or so…

Glaze with a beaten egg, sprinkle with poppy seed, or sesame seed, or both, or neither….

Bake at 350 for 45-60 minutes, until golden brown. They will make a hollow sound when you tap ‘em if they are done.