A story is recounted in Yevamot 121a of Raban Gamliel on a boat. From a distance, Raban Gamliel sees another boat, shattered. A shipwreck. Knowing somehow that his colleague and friend Rabbi Akiva had been traveling on that boat, Raban Gamliel grieves for the wise and prolific Rabbi Akiva. But when Raban Gamliel disembarks onto dry land, he is surprised to encounter Rabbi Akiva, alive and well, who comes to sit before him and discuss halakhah.

“My son,” Raban Gamliel asks, amazed, “Who brought you up from the water? Who rescued you?!”

To which Rabbi Akiva responds:

דַּף שֶׁל סְפִינָה נִזְדַּמֵּן לִי וְכׇל גַּל וְגַל שֶׁבָּא עָלַי נִעְנַעְתִּי לוֹ רֹאשִׁי

“A daf from the boat came to me, and I bowed my head at each wave that came over me.”

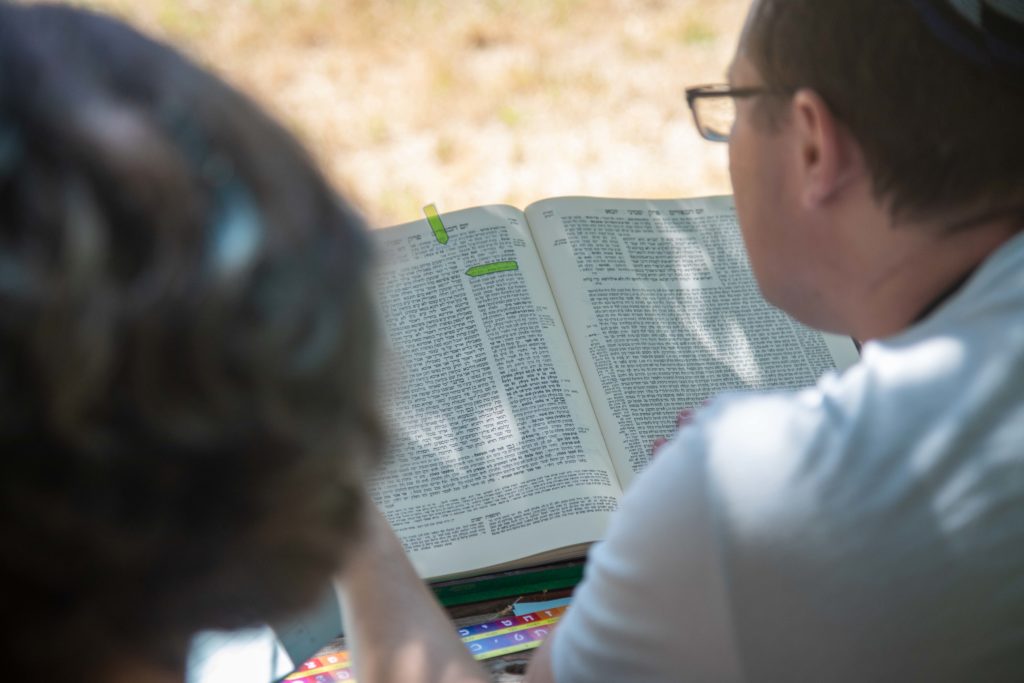

The word daf (דַּף) comes from the root דפף, to hammer or join. As a noun, a daf can be a board or a plank, a hammered slab of wood joined together to create a new structure, such as a boat. There’s no question that on the surface level, Rabbi Akiva is describing a plank of wood that he was able to grab onto during this dangerous shipwreck, which kept him afloat as he endured the passing waves. However, in later Hebrew, daf also comes to mean a column of text in a scroll, or a leaf/page of a book. At SVARA we’re intimately familiar with daf as the word used across the Jewish diaspora for a page of Talmud.

I’ve always understood this story as a parable for a life filled with learning. We’re afloat in this vast sea of uncontrollable circumstances. Sometimes the waters that surround us are trecherous, sometimes they are placid, and often they are everything in between. This story teaches us to reach for our spiritual practice of learning when the going gets hard, to hold tight. Hold onto the daf, reach for Talmud Torah, I hear Rabbi Akiva saying, to keep you afloat through all that comes.

I’ve experienced this before. Torah study has saved my life by offering me a flotation device–– a way to stay present, active and engaged with my ancestors and chevrutas even during the most wrenching or uncertain moments. I’ve felt like Rabbi Akiva, gripping the daf as the waters of loss, change, or fear enveloped me, my learning buoying me from this wave to the next.

This past week I had the privilege of learning with Imani Romney-Rosa Chapman, a racial equity educator, organizer, and spiritual leader. Imani was teaching her Torah on synagogue-based antiracism initiatives, and the work of developing accountability within multiracial communities, to a small group of rabbis through the Synagogues Rising network. She opened her teaching with Exodus 36, and asked us, “What can we learn from the building of the mishkan that would help us in building antiracist community within our synagogues?”

In Exodus 36, Moses authorizes Bezalel, Oholiab, and all skilled artisans in the Israelite community to construct the mishkan according to G!d’s instructions. The people bring free-will offerings each morning to the tabernacle in order to contribute to the process. Eventually, the offerings are too much for the artisans, and Moses instructs the camp: “No more offerings! It is enough.” The people pause their giving, and the mishkan is built.

Each person in the room had a different answer to Imani’s question. Someone described this as a story about communal willingness and the importance of respecting boundaries when they are set. Another person picked up on the hierarchical nature of leadership in the story, and wondered whether Moses and the artisans wrongly gate-kept the true gifts of the people. Someone else noticed the words “וְכֹל אִישׁ חֲכַם־לֵב” to describe the artisans in the first verse, and reflected on the work of antiracism and accountability happening from within the embodied wisdom of our hearts, rather than the reptilian, reactive parts of our brains.

Learning this way, just days after the white supremacist massacre in Buffalo, I felt the potential of Torah learning to hold us up in the hardest of times. We are shipwrecked, again, nearly drowning in the waters of grief, despair, helplessness, heartbreak, and exhaustion. As a multiracial global Jewish community, we are each impacted differently by this attack, but let us be clear that the attack is on our collective whole. It is an assault on all our people–– Black and POC people, queer and trans people, Jewish people–– motivated by a deeply racist, anti-Black, and antisemitic ideology.

As we learned Exodus 36 through the lens of Imani’s question, I wondered what it would be like to study every parsha of the year asking: “What can we learn from this parsha that would help us in building antiracist communities?” I wondered what we’d learn from asking the same question of every sugya or daf of Talmud. What guidance, truths, and principles; what questions, role models, and cautionary tales would our tradition reveal to us; what would we reveal to ourselves and each other if we put antiracism at the center of all Torah learning?

There was no immediate conclusion to our exploration of Exodus 36. Instead, we gathered around this ancient and archetypal story to unpack and reflect on our failures and successes in the journey of building antiracist institutions and communities. We let the narrative of Torah guide us toward a Torah of humility, exploration, and the goal of principled action. We took up Ben Bag Bag’s invitation in Pirkei Avot:

הֲפֹךְ בָּהּ וַהֲפֹךְ בָּהּ, דְּכֹלָּא בָהּ. וּבָהּ תֶּחֱזֵי, וְסִיב וּבְלֵה בָהּ, וּמִנַּהּ לֹא תָזוּעַ, שֶׁאֵין לְךָ מִדָּה טוֹבָה הֵימֶנָּה

Turn it and turn it, for everything lies within it. Look into it and become old and gray with it, and do not move away from it, for you have no better attribute [מִדָּה] than it. (Avot 5:22)

I think Rabbi Akiva, rescued by a daf in a shipwreck, would affirm that even when it feels like nothing can speak into the void of this grief, rage, and terror, we can hold onto Torah, if not for dry ground then at least as a way to keep our heads afloat above the waves of hopelessness. And we can ask things of Torah–– we can ask it to be a tradition that speaks directly to our experiences, to our aspirations for better communities and a better world. We can ask that Torah open us to vulnerability, honesty, synthesis, and self-reflection. To courage, joyfulness, and radical imagination. To settled nervous systems and hearts of wisdom. These are some of the מִידוֹת (attributes) it takes to build communities of accountability. As we grieve and do the work, may we too reach resiliently for the daf, and may it support us to ride these waves toward a future we are transforming together in community.