In addition to my love of Mishnah and Talmud, I am passionate about Jewish contemplative practice. I am a Mussar practitioner and facilitator and am also in my second year of a three-year Jewish mindfulness and meditation teacher training program. My Mussar practice grounds me and helps me remain accountable to myself, to others, and to The Divine in all that I do. Just as mindfulness practice asks us to choose an anchor in our practice—something we return to again, again and again— Mussar has chazarah built right in. And as we say at SVARA, chazarah is where the magic happens.

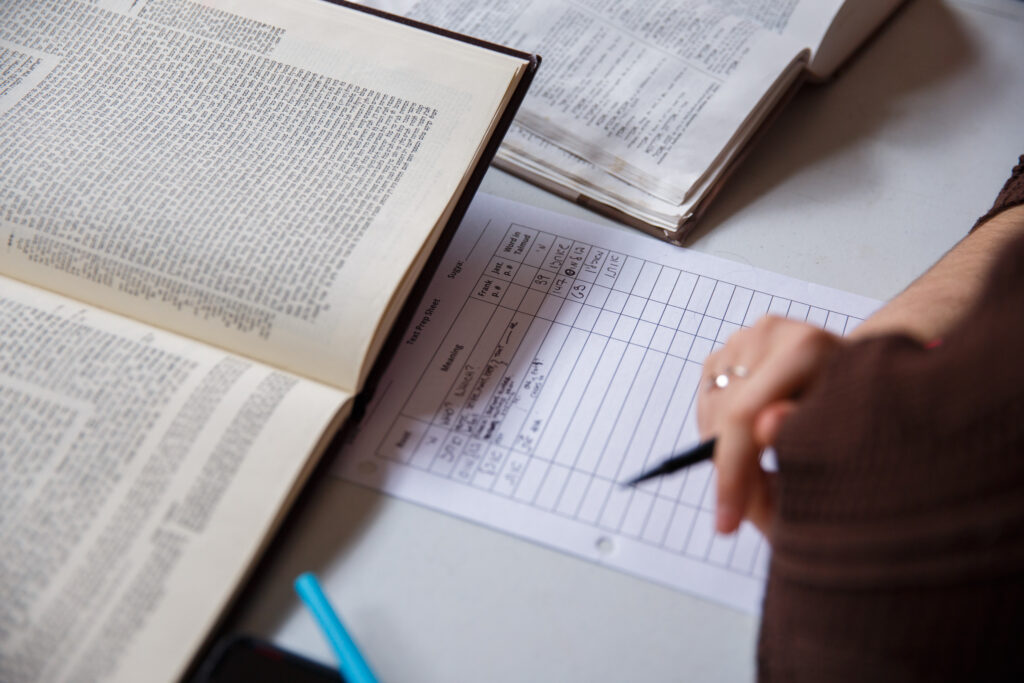

In my Mussar work, chazarah happens through a daily cheshbon hanefesh or soul accounting practice in which I reflect on the day and make a note about the times I showed up aligned with my best self and values as well as those times when I didn’t. In this review, I am always bringing tremendous self-compassion. This, too, is what we do at SVARA when we review a sugya we’re learning. Though we are accountable to getting the words right—and allowing them to live and breathe through us—when we reach the end of our recitation, we clap each other up and begin again with tremendous care and compassion, knowing that in doing so we illustrate our Rabbis’ promise—we will never forget you, you are on our minds and we are on yours, we return to you and you return to us.

Chazarah is holy precisely because of these precious opportunities to start again. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s learning for its own sake—lishma. So, too, in my practice of Mussar, I’m not trying to get to a place where I am perfectly balanced in each middah or soul trait. That’s impossible. Instead, I’m trying to hold myself accountable with love and compassion to living a life aligned with my higher soul. Hopefully, this desire manifests in the world as it is through how I show up. This is not a spiritual practice that asks us to remove ourselves from the world but instead to encounter it as it is with radical humility. I know I’m going to mess up all the time—we all do. Mussar helps me reorient when I inevitably do. If there’s one space where I am particularly aware of this, it’s when I teach.

The meditation practice I am working with is currently focused on the body. We’re being asked to practice noticing what arises in the body as we practice and to observe our somatic responses as we teach.

Knowing that the body is far from a neutral place, I find myself grateful to be invited to hold and acknowledge all that is true and all that arises moment by moment. Mussar has taught me that truth grows from the ground—deeply rooted, ever-present, often complex and difficult to put into words. We must always be seekers of truth, knowing as our rabbinic ancestors teach us that these are the words of the living G-d. Talmud study as spiritual practice trains us similarly to seek truth. We hold the multifaceted opinions of our rabbinic ancestors, making our way through complicated and sometimes perplexing texts. We learn to concentrate on studying for its own sake as we do so, using the text as our anchor. When we do chazarah, we return, again and again.

Recently, SVARA’s Mishnah Collective learned a difficult text. Realizing I would be teaching that day, I found myself simultaneously nervous and feeling a clarity about how I would approach the text that honestly surprised me. I knew that the text would present challenges. I noticed myself grasping at those challenges—if I accounted for every possible thing in this short but powerful text that might be upsetting, could I avoid the hard shiur at hand? Would things go terribly awry if I didn’t give an extensive pre-teach? If I preempted the text with a lot of framing, would I be inadvertently biasing the learners? All of these questions floated around and, even as they did, I found myself, unexpectedly, sinking deeper into my own knowing that this text would land as it would and that I could hold the container of the learning. Knowing that in my bones prompted a new series of reflection questions for myself.

What is mine to hold and what is mine to let go of? As a teacher and guide, I am responsible for creating a co-creative learning space that challenges and inspires. Inevitably, we bring our own reactivities and activations with us. How much of that, if any, can I anticipate? What strategies can I weave into my teaching to help learners navigate and respond to what arises? What can I trust will be held by my learners in their own unique ways?

One of the core practices of Mussar that is done alongside the soul-accounting is saying a focus phrase or morning affirmation daily. These phrases typically relate to the middah or soul trait a person is practicing with. One that I return to again and again relates to anavah, or humility. In the Jewish tradition and the lineage of Mussar specifically, anavah is not about retracting the self to fit a mold or diminishment of the self. Rather, it is about knowing what my place is—no more, no less—and what my space is—no more, no less. In my understanding, it is about inhabiting my space and place in a right-sized way, aligned with who I am at my core. This is no less applicable in teaching.

Rooted in the humility that comes with my particular orientation to teaching, I understood that this was an incredible opportunity for practice and that my role as a teacher and guide could provide a dugma—an example—for others to follow. I no longer felt compelled to ensure that my learners would agree with my interpretation and historical contextualization of the text. What mattered most was that through my own humility, I was able, I hope, to show up to that teaching anchored by a profound wisdom that what emerged would help us all grow in our immersion in the words of Torah.

Practice implies discipline. We show up when we really don’t want to. We show up when it’s hard. We show up because we’re accountable for our chevruta’s learning. We make commitments because this engenders trust.

The daily discipline of the Mishnah Collective is a practice in so many ways. When we arrive, we set aside what we had been doing previously. We orient ourselves towards the practice of learning and uncovering. We may set intentions or kavanot for our practice—that’s the role of the dedication. We recognize that we’re not aiming for an ultimate and final destination. We are immersing ourselves in the sea of Torah, grappling as we do with the beauty and the challenge, the complicated and the straightforward.

May we continue to return again and again to our learning, and may it serve as an anchor for us. As we do so, may the knowing in our own bones be a guide for us as we hold sacred containers of learning and practice. Ken yehi ratzon.