The mornings come quickly these days. A combination of a 5:15 a.m. alarm, the desire to have adult time after bedtime, poor sleep on a household level, and increased stress means that most mornings I’m startled by my phone alerting me of the time.

On the better mornings, I wake up a few minutes before my alarm or an hour before my kids. On the best mornings, I make my way downstairs to the home gym in the corner of our dining room that once hosted Shabbat dinners but now functions more as an office or mail room or gym. I give myself a pep talk about the power of movement in my life experience and set to the task of reinhabiting my body and connecting to a more whole version of myself.

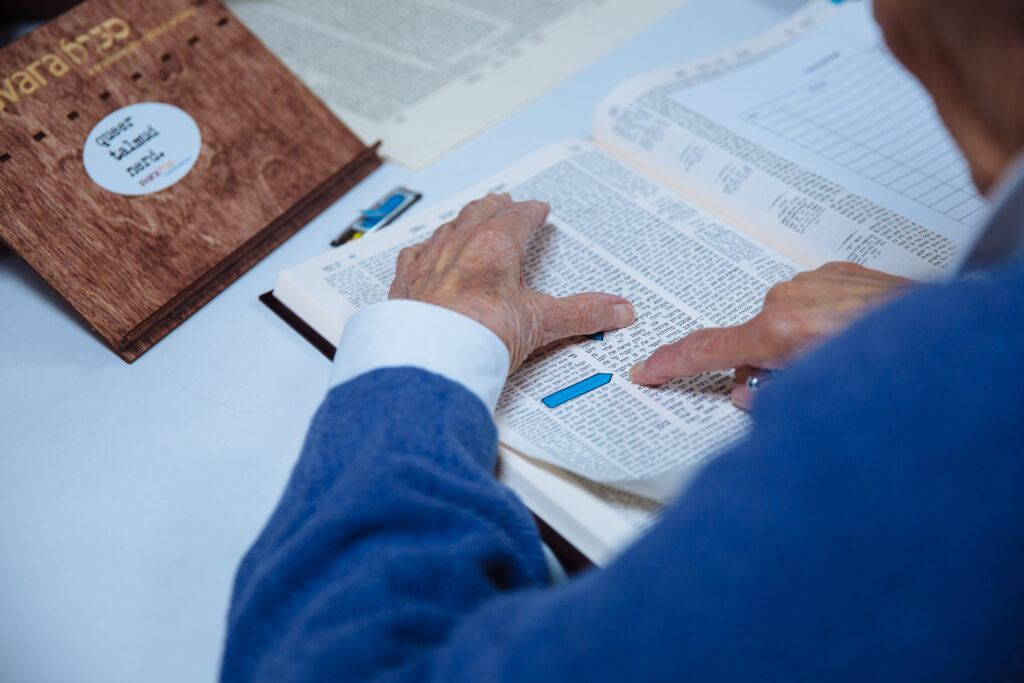

The Shulchan Aruch, a foundational 16th-century code of law compiled by Yosef Karo, opens:

יתגבר כארי לעמוד בבוקר לעבודת בוראו שיהא הוא מעורר השחר

One should strengthen themself like a lion to get up in the morning to serve their Creator, so that it is they who awaken the dawn (Orach Hayyim 1:1).

The Mishnah Brurah, a commentary on this section of the Shulchan Aruch, offers that we should awaken “to serve their Creator” because that is why we were created! We should awaken with a sense of our divine purpose, however we understand that.

These days, however, I sometimes struggle to find my purpose amidst the pain and devastation on a global level, the overwhelming amount of news I am taking in, and the work of internalizing or processing the death in Gaza and Israel. How should I be moving from my deeply held clarity that my purpose is to teach Torah that supports and embraces Jews that have often been marginalized? Perhaps, more honestly, what I’m struggling with is following that path knowing that it leads me directly into distrust and dehumanization in the Jewish community. And some days, both the physicality of bounding out of bed like a lion and strength to fulfill some sense of divine purpose feel aspirational.

I have found grounding and strength in a familiar text. In a moment where a call to center “peoplehood” and “unity” had been made, there is a similar call to distance or disassociate from Jews with different political opinions. If my purpose is to live Torah and help others do the same, I’ve wondered how we live Pirkei Avot 5:17:

כָּל מַחֲלֹקֶת שֶׁהִיא לְשֵׁם שָׁמַיִם, סוֹפָהּ לְהִתְקַיֵּם. וְשֶׁאֵינָהּ לְשֵׁם שָׁמַיִם, אֵין סוֹפָהּ לְהִתְקַיֵּם. אֵיזוֹ הִיא מַחֲלֹקֶת שֶׁהִיא לְשֵׁם שָׁמַיִם, זוֹ מַחֲלֹקֶת הִלֵּל וְשַׁמַּאי. וְשֶׁאֵינָהּ לְשֵׁם שָׁמַיִם, זוֹ מַחֲלֹקֶת קֹרַח וְכָל עֲדָתוֹ

Every dispute that is for the sake of Heaven, will in the end endure; But one that is not for the sake of Heaven, will not endure. Which is the controversy that is for the sake of Heaven? Such was the controversy of Hillel and Shammai. And which is the controversy that is not for the sake of Heaven? Such was the controversy of Korach and all his congregation.

Amongst the many explanations of why Hillel and Shammai are used as the example of controversies for the sake of heaven, what sticks out to me today is that Hillel and Shammai are colleagues. Their disagreements vary in scope and consequence, yet they all exist within an accepted container. Though they disagree regarding how to live Torah, they never question whether the other is striving for that same vision. Hillel, Shammai, and their respective schools center relationship and common purpose amidst difference.

As I look out at the Jewish world, I wonder if we are holding the same vision of the world we are building. Or, at least, if we can trust that all Jews yearn for Jewish safety. If we can see one another, throughout the diaspora and Israel, as holding a shared hope for a world in which Jews, alongside all others, can safely practice their religion, express their cultures, and generally live lives of dignity.

If we aren’t holding similar worldviews or can’t lean into that trust—something I certainly struggle with—perhaps we can learn about other approaches from our tradition. Three come to mind.

First, what can we learn from Korach and the people assembled with him? Korach relies on confrontation and asserting his own power instead of engaging Moses and Aaron as leaders through relationship. He gives voices to the people’s concern but doesn’t necessarily make space to understand Moses and Aaron’s intent. Korach is acting righteously, asserting the holiness of all the Israelites, but is often read as doing so from a place of anger and not from a grounded place of curiosity or clarity of purpose. If we understand Korach’s strategy and the role of polarization in organizing, just as I believe in the mass protests we are seeing today, we can see him doing the holy work of asserting his place in the community, the way those on the streets are doing so today. Though his attempt may not be an example of an enduring controversy, we can reframe it as a strategy to call our community to a different or even better version of itself.

Second, absent a joint world view, I believe we have the obligation to try and create one. This vision is at the core of combatting the oppression that exists in the world. A conversation about what values we share, how those get implemented, and where our implementation ideas differ might just qualify as an argument for the sake of heaven.

Finally, we can heed the Shulchan Aruch’s call and do our best to wake up with the intention of connecting to our purpose, to Torah, and to Hashem, however you understand those things. By doing so, we both set ourselves up to feel more grounded and alive to the tremendous potential of each and every day, and contribute to a communal embodiment of kiddush Hashem and ahavat Torah, the uplifting of divinity and wisdom, in our world: a world of justice, dignity and love.